Plastic bottles, soil, water, decomposers, and small plants are beginning to take over the Environmental Science classroom as students start assembling ecocolumns — a signature project in Ms. Román’s Environmental course. Like seedlings sprouting, the class is growing. Now in its second year, the class has doubled in size, upgrading from the fishbowl to an actual classroom.

Environmental Science became a class in the spring of 2025, created by Ms. Román after she noticed a gap in the science department. “I just saw a need,” she said. “Environmental science is so relevant to everyone’s lives, and we didn’t really have a class for that.”

The course covers a wide range of topics, including ecology, biodiversity, sustainability, energy usage, and pollution. However, a significant component of the class is the ecocolumn project, which allows students to apply these concepts tangibly.

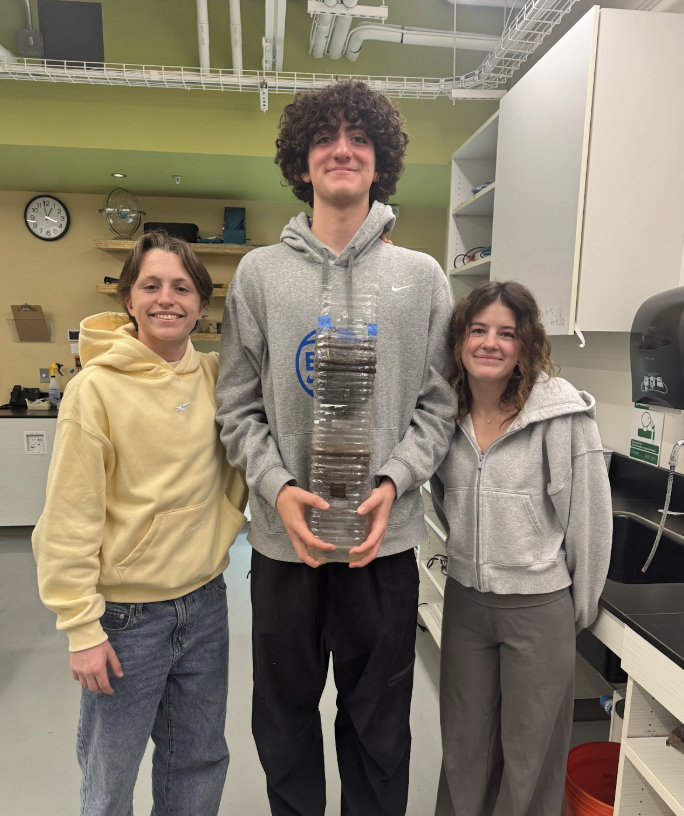

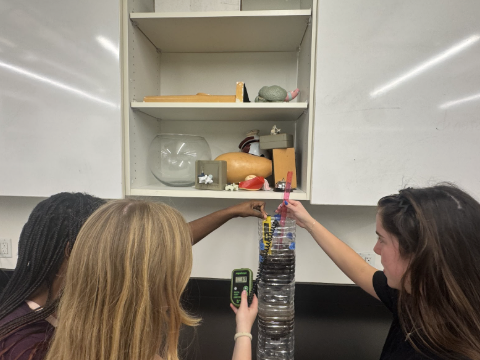

The goal of the ecocolumn project is to build a self-sustaining ecosystem. Using three one-liter plastic bottles, students cut and stack them into a vertical model, with each layer representing a different part of an ecosystem. The top level contains soil, where students plant small plants and add decomposers. The middle level is filled with sand, acting as a natural filter for water. The bottom level holds water, where students will later add aquatic plants, snails, and possibly fish.

An ecocolumn takes about three class periods to build. Once completed, the columns allow students to observe how matter and energy move through an ecosystem. “The goal is to create a model for real-life ecosystems,” Ms. Román explained, “and see all of the relationships and cycles that are needed to keep an ecosystem thriving.”

Although building the ecocolumns takes about three class periods, the project continues for five weeks or more. During that time, students collect and record data almost daily and enter it into a table. They measure soil fertility, pH, temperature, plant growth, dissolved oxygen, and nitrate and nitrite levels. As the project progresses, students will use the data to create graphs that analyze how small changes affect an ecosystem over time.

For many students, this hands-on approach is what made the class appealing in the first place. “I chose environmental science because it has a lot of hands-on learning,” said junior Braden Shuster. Junior Wesley Tarbell shared a similar motivation and added, “I chose it because I like the environment, and I wanted to learn more.”

Last year, Environmental Science began with only six students; this year, however, enrollment has doubled. Ms. Román believes that the increase is due to growing interest in environmental issues. “You hear about environmental science every day…mostly about the problems, but I’m hopeful that this class focuses more on the solutions and the science behind it,” she said.

Student interest reflects Ms. Román’s belief about the increase in enrollment, as the focus on real-world impact drew junior Teagan Roeder to the course. “I chose environmental science because I am interested in sustainability,” she said. “We are learning about policies worldwide that contribute to cleaning up the environment, and we’re building terrariums.”

With a larger class size, Ms. Román is adjusting her teaching approach and looking for new opportunities to take learning beyond the classroom. She hopes to introduce new activities, such as collecting soil samples around campus or testing water from the canal. “I want them to learn practice skills they can use after they graduate,” she said.

As the Environmental Science class continues to grow, so do its projects, branching out in both size and scope. Through hands-on experiments such as the ecocolumn project, students are not only learning about environmental science but also actively practicing it.